Few immigrants have interpreters like me in court, and that hurts us all

Recently, the U.S. Senate passed a bill aimed to make it more difficult for migrants to enter the U.S. and request asylum.

But this bill does nothing to address one of the major factors that slows efficiency in the immigration system: lack of adequate interpretation services for applicants.

A number of years ago, I was introduced to Hugo, a Mexican migrant facing deportation. Hugo was lucky to be represented by a pro-bono lawyer, which is rare for individuals in detention.

But there was a deeper problem: he couldn’t communicate with his counsel. Or the judge. Or any of the officials deciding his fate.

Hugo lacked an interpreter to help him

He’d been categorized as a Spanish-speaker, but his native language was Mixe, an Indigenous language from the Mexican state of Oaxaca.

Hugo, whose name has been changed to protect his identity, understood a few Spanish phrases, but mostly he was in the dark about what was happening to him.

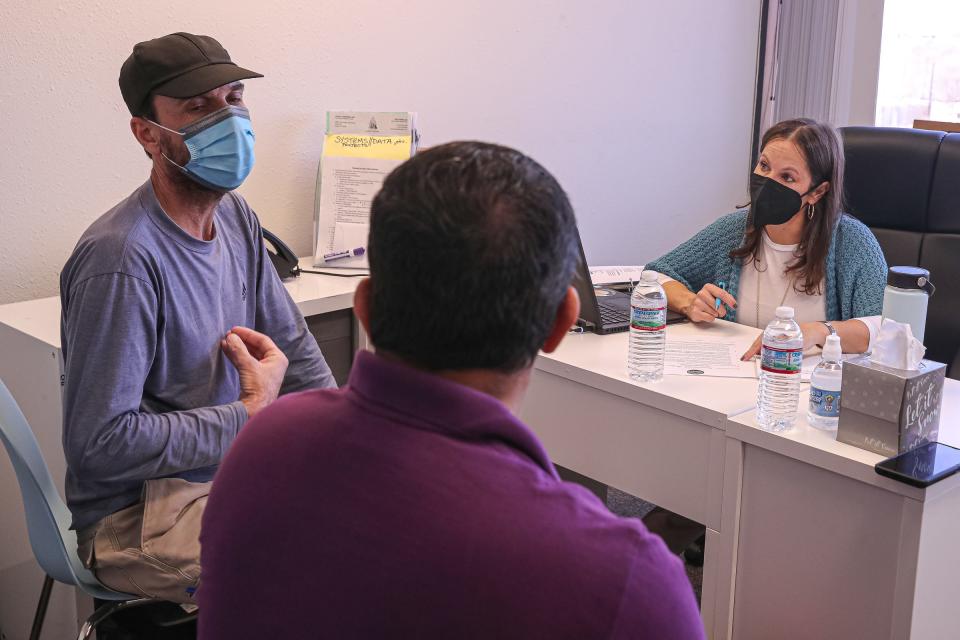

By U.S. law, anyone facing deportation or claiming asylum has the right to understand and “meaningfully participate” in the legal process. I’m a translation and interpretation expert, so I was asked to determine Hugo’s Spanish proficiency.

After a thorough evaluation, I determined that he couldn’t handle basic communication tasks in Spanish, let alone understand court proceedings. Hugo spent a year in detention before the court dismissed the case for lack of interpreter.

Federal law requires that the government provide meaningful access to people with limited fluency in English. Frequently, migrants report having no interpreter available if they’re detained or if they present themselves at the border.

Mexico alone has 68 Indigenous languages. Latin America has hundreds more. Even Spanish-speaking migrants can have trouble understanding U.S. Customs and Border Protection agents, most of whom are not certified interpreters.

Initial interviews with migrants are critical

In fact, many agents have only taken a mandatory Spanish course at the Border Patrol Academy. This often is not enough to reach the comprehension and fluency level required to interact with a diverse Spanish-speaking population.

There are other challenges — like relying on the person in charge of your custody in order to understand your rights.

Initial interviews with migrants are critical.

Many of these initial interviews evaluate whether someone has a “credible fear” of returning to their country of origin, which may allow them to pursue asylum. If a migrants appear before a judge and their testimony in court doesn’t match their original interview, they can be deemed not credible and denied asylum.

The problem is compounded by the increase in the number of migrants from historically atypical countries, such as Nicaragua, Haiti and Turkey. In fiscal 2022, these accounted for 40% of total border encounters, up from 3% in FY 2011.

Arizona border bill: Does nothing to secure the border

A 2016 report from the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom found numerous instances of inaccuracies and mistranslations during these initial interviews. It mentioned a case of a 4-year-old child who said he had come to the United States to work.

The tens of thousands of migrants who await their hearings in a detention facility have an even greater disadvantage. Seventy percent of these individuals lack legal representation, which means they have no attorneys.

Detainees are supposed to receive translation services over the phone, but there’s a severe lack of interpreters and little oversight.

We must understand asylum seekers to help them

The lack of language access that Hugo faced is not only a problem for many migrants; it also means that the government is less efficient as it aims to reduce the significant backlog of asylum cases.

The federal government has failed to develop protocols or resources that guarantee meaningful linguistic access even for the most commonly spoken languages like Spanish.

We can’t know if someone merits asylum if we can’t understand them. Adjudicators, law enforcement and judges need access to accurate information to make fair decisions.

People fleeing trauma and hardship should be able to communicate clearly with the people in charge of their fate. They should be able to participate in the legal process.

It was only because Hugo was lucky enough to have an attorney that he was able to have his fluency examined.

By not providing sufficient language services, we’re stripping away their fundamental rights and setting these individuals up to fail from the start.

As a modern democracy, we can — and must — do better.

Jaime Fatás-Cabeza is a specialist in translation and associate professor at the University of Arizona. He is the former director of the undergraduate program in Translation and Interpretation and a faculty member at the UA National Center for Interpretation, Testing, Research, and Policy. He is a certified federal court judicial interpreter and translator by the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts. Reach him at jfatas@arizona.edu.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Arizona needs more interpreters to accurately process immigrants